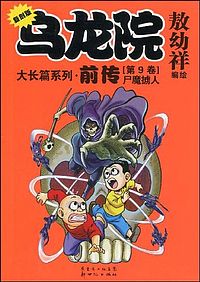

乌龙院大长篇系列·前传(第12卷) 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

乌龙院大长篇系列·前传(第12卷)电子书下载地址

内容简介:

《乌龙院大长篇系列·前传(第12卷):丐帮奇遇(复刻版)(小开本)》内容简介:乌龙院师兄弟俩在洗碗期间大开人鼠大战,店小二有意刁难,老板娘都睁一只眼闭一只眼!不胜感激的他们却无意中发现老板娘竟跟魔教有关联,赶紧连夜逃走,不料被发现了……武艺高强的叫花子老伯出手相救,究竟是何方神圣呢……

书籍目录:

暂无相关目录,正在全力查找中!

作者介绍:

暂无相关内容,正在全力查找中

出版社信息:

暂无出版社相关信息,正在全力查找中!

书籍摘录:

暂无相关书籍摘录,正在全力查找中!

在线阅读/听书/购买/PDF下载地址:

原文赏析:

暂无原文赏析,正在全力查找中!

其它内容:

书籍介绍

《乌龙院大长篇系列·前传(第12卷):丐帮奇遇(复刻版)(小开本)》内容简介:乌龙院师兄弟俩在洗碗期间大开人鼠大战,店小二有意刁难,老板娘都睁一只眼闭一只眼!不胜感激的他们却无意中发现老板娘竟跟魔教有关联,赶紧连夜逃走,不料被发现了……武艺高强的叫花子老伯出手相救,究竟是何方神圣呢……

精彩短评:

作者:书庭 发布时间:2019-06-16 18:46:42

水彩和文字都好温柔又美丽

作者:缓缓姑娘 发布时间:2018-10-15 09:26:55

有助于人际关系的提升

作者:颍原真吾 发布时间:2017-01-24 17:55:12

鱼,我所欲也;熊掌,亦我所欲也。二者不可得兼,舍鱼而取熊掌者也。生,亦我所欲也;义,亦我所欲也。二者不可得兼,舍生而取义者也。生亦我所欲,所欲有甚于生者,故不为苟得也;死亦我所恶,所恶有甚于死者,故患有所不辟也。如使人之所欲莫甚于生,则凡可以得生者何不用也?使人之所恶莫甚于死者,则凡可以辟患者何不为也?由是则生而有不用也,由是则可以辟患而有不为也。是故所欲有甚于生者,所恶有甚于死者。非独贤者有是心也,人皆有之,贤者能勿丧耳。

作者:阮戴安 发布时间:2023-11-30 15:42:01

崔恩荣解剖人际关系的笔触里包裹着克制又清醒的温情,她写人际关系的脆弱与无可挽回,人与人之间有太多无法跨越的天堑,却也写世易时移后想到我们曾经互相取暖的余温。最喜欢《601,602》和《你好,再见》两篇。

作者:或彡 发布时间:2021-10-31 23:59:25

探索摄影技术,让画面更加精彩——各种鸟飞越文明地标、真正的鸟的视角、着眼于大众视野之外的鸟类行为(如跟着海里的掠食者捡吃剩的猎物、偷灰熊抓的鲑鱼)/后记的拍摄经历值得一看!在猛禽身上绑摄像头,人用滑翔机教驯养的鸟飞…… 因为禽流感的阻碍,不得不搁置拍摄计划,“这种情况非常令人沮丧,而我们却一点办法都没有”,观照当下的疫情,唉。

作者:C++ 发布时间:2009-07-31 14:36:04

学习

深度书评:

福山写的《Why Nations Fail》书评

作者:frances 发布时间:2012-12-07 21:03:27

Acemoglu and Robinson on Why Nations Fail

Francis Fukuyama

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have just published Why Nations Fail, a big book on development that will attract a lot of attention. The latest fad in development studies has been to conduct controlled randomized experiments on a host of micro-questions, such as whether co-payments for mosquito bed nets improves their uptake. Whether such studies will ever aggregate upwards into an understanding of development is highly questionable. By contrast, Acemoglu and Robinson have resolutely focused on only the largest of macro questions: how contemporary institutions were shaped by colonial ones, why it was that regions of the world that were the richest in the year 1500 were among the world’s poorest today, or how rich elites were ever persuaded to redistribute their wealth. In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson restate and enlarge upon earlier articles like “The Colonial Origin of Institutions” and “Reversal of Fortune,” but in contrast to their academic work, the new book has no regressions or game theory and is written in accessible English for general readers.

Acemoglu and Robinson (henceforth AR; Simon Johnson of the old AJR team dropped out of this volume) have two related insights: that institutions matter for economic growth, and that institutions are what they are because the political actors in any given society have an interest in keeping them that way. These may seem like obvious statements, but many people in the development business haven’t gotten the message. Among development specialists there is what AR term the “ignorance” hypothesis: failure to develop is the result of not knowing either what good policies are (this was the old Washington Consensus) or, now that the focus has shifted to institutions, what good institutions are or how to create them. Many development agencies act as if leaders in developing countries want to do the right thing, if only they knew how, and that development assistance should therefore consist of sending smart people from places like Washington out to teach them, perhaps accompanied by some structural adjustment arm-twisting.

By contrast AR argue that bad institutions are the product of political systems that create private gains for elites in developing countries, even if by doing so they impoverish the broader society. (Think Nigeria, which has many multimillionaires while 70 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.) Doing the “right thing” would take away the rents they receive, which is why no amount of hectoring or threats to withhold the next loan tranche has much effect on their behavior. They are making almost the identical point to the one made in the 2009 book Violence and Social Orders by Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast (NWW), who argue that most underdeveloped societies are what they term “limited access orders” in which a rent-seeking coalition limits access to both the political and economic system. Indeed, I see no real difference between the “extractive/inclusive” distinction in AR and the “limited/open” access distinction in NWW.

This conclusion about the primacy of institutions and politics for development has important implications for policy as AR point out. If growth is a byproduct not just of good policies like trade liberalization, which can in theory be turned on like a light switch, but rather of basic institutions, then the prospects of foreign aid look dim. Bad governments can waste huge amounts of well-intentioned outside resources; indeed, the flow of aid dollars into poor countries can undermine governance by undercutting accountability, thereby leaving societies worse off than they would otherwise be. As the American nation-building efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq have indicated, moreover, foreign efforts to help construct basic institutions are an uphill struggle. Bad institutions exist because it is in the interests of powerful political forces within the poor country itself to keep things this way. Hamid Karzai understands perfectly well how clean government is supposed to work; it’s just that he has no interest in seeing that happen in Afghanistan. Unless the outsiders can figure out a way to change this political calculus, aid is largely useless.

So far, so good. AR have done a great deal over the years to focus the attention of both theorists and policymakers on institutions, and to shape the emerging consensus on the importance of politics to growth within the economics profession. It is, then, very disappointing that their more fully fleshed out book fails to go very much further than these broad conclusions, skirting critical issues of exactly what sort of institutions are necessary to promote growth, and failing to come to grips with some critical historical facts.

The first problem with their analysis is conceptual. They present a sharply bifurcated distinction between what they call good “inclusive” economic and political institutions, which are sometimes also labeled “pluralistic,” in contrast to what they call bad “extractive” or “absolutist” ones. Unfortunately, these terms are way too broad, so broad indeed that AR never provide a clear definition of everything they encompass, or how they map onto concepts already in use. “Inclusive” economic institutions, for example, seem to include formal property rights and court systems, but also have to do with social conditions that allow individuals access to the market such as education and local custom. “Inclusive” political institutions would seem to imply modern electoral democracy, but they also include an impersonal centralized state as well as access to legal institutions, and forms of political participation that fall well short of modern democracy. We find, for example, that England following the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 was incipiently inclusive, despite the fact that well under ten percent of the population had a right to vote. When AR first used the term “extractive” in their early articles, it referred to truly extractive practices like the mines of Potosí or the sugar plantations of the Caribbean which extracted commodities out of the labor of slaves. In the current book extractive seems to mean any institution that denies any degree of participation to citizens, from tribal communities to ranchers in 19th century Argentina to the contemporary Chinese Communist Party.

Since each of these broad terms (inclusive/extractive, absolutist/pluralistic) encompasses so many possible meanings, it is very hard to come up with a clear metric of either. It also makes it hard to falsify any of their historical claims. Since more real-world societies are some combination of extractive and inclusive institutions, any given degree of growth (or its absence) can then be attributed either to inclusive or extractive qualities ex post.

The use of such broad categories and the failure to distinguish between the different components of political “inclusion” greatly diminish the book’s usefulness, because one wants to know how these components individually affect growth, and how they interact with one another. There is for example a large literature comparing the separate impacts of a modern state, rule of law, and democracy on growth, which tends to show that the first two of these factors have a far greater influence on outcomes than democracy. There is in fact a lot of reason to think that expansion of the franchise in a very poor country may actually hurt state performance because it opens the way to clientelism and various forms of corruption. The Indian political system is so inclusive that it can’t begin major infrastructure projects because of all the lawsuits and democratic protest, especially when compared to the extractive Chinese one. Furthermore, as Samuel Huntington pointed out many years ago, expanded political participation may destabilize societies (and thereby hurt growth) if there is a failure of political institutions to develop in tandem. All of the good things in the “inclusive” basket, in other words, don’t necessarily go together, and in some cases may be at odds. You never get much hint of this in Why Nations Fail, however, since the authors seem to argue the more inclusion the better, along any of its axes.

Like many other works making use of history but written by economists, the AR volume contains some pretty problematic facts and interpretations. It makes the case, for example, that Rome shifted away from an inclusive Republic towards absolutist Empire, and that this was then responsible for Rome’s subsequent economic decline. Leave aside the fact that Rome’s power and wealth continued to increase in the two centuries after Augustus, and that its eastern wing managed to hold on remarkably until the fifteenth century. It can be argued that the shift from the narrow oligarchy of the Republic to a monarchy with highly developed legal institutions actually increased access to the political system on the part of ordinary Roman citizens, while solving the acute problem of political instability that bedeviled the late Republic.

Similarly, following on a tradition begun by Douglass North and Barry Weingast, AR point to the Glorious Revolution of 1688/89 as a critical juncture marking both the establishment of secure property rights and an “inclusive” political system. The latter point is fair enough, but English property rights were rooted in a much older tradition of common law dating from the Norman invasion, and had created a strong commercial civilization well before 1689. The Glorious Revolution was much less important in establishing the credibility of property rights per se, than of the Crown as a borrower, which explains why English public debt exploded in the century following that event.

Given their overall framework, the hardest thing for AR to explain is contemporary China. China today according to them is more inclusive than Maoist China, but still far from the standard of inclusion set by the US and Europe, and yet has been the fastest growing large country over the past three decades. The Chinese restrict access to the market, engage in financial repression, fail to secure property rights, have no Western-style rule of law, and are ruled by a non-transparent oligarchy called the Communist Party. How to explain their economic success? Rather than see this as a threat to their model (i.e., more inclusion, more growth) AR pull a slight of hand by arguing that Chinese growth won’t last and that their system will eventually come crashing down (like Rome did, after about 200 years?). I actually agree that China will eventually crash. But even if that happens, a theory of development that can’t really explain the most remarkable growth story of our time is not, it seems to me, much of a theory.

The broad conclusions of Why Nations Fail are, thus, incontrovertible and of great importance to policy (which is why, incidentally, I gave it a positive blurb). One only wishes then that the authors had made better use of basic categories long in play in other parts of the social sciences (state, rule of law, patrimonialism, clientelism, democracy, and the like) instead of inventing neologisms that obscure more than they reveal.

在愤世嫉俗与英雄主义间摇摆的东欧奇幻

作者:Шатов 发布时间:2021-12-17 20:36:05

配图是俄罗斯版《猎魔人》的插图

《猎魔人》是我自《魔戒》和《冰与火之歌》后读过的第三部西式奇幻。和很多人一样,我对这个系列的了解最初来自cdpr的游戏,此外还有一个对它感兴趣的原因,那就是作者是个波兰人。事实上这点确实未让我失望。猎魔人小说最吸引我的点,首先就是原著中浓厚的波兰和斯拉夫特色,尤其是波兰人特有的对地缘政治、反战反歧视等问题的思考。和很多看似在写“史诗”,但其中的社会政治描写完全经不起推敲的幻想小说不同(这里不点名批评部分美国作者)。《猎魔人》的世界看似高魔,但反映的社会政治现象却十分具有现实感和现代感。例如书中的民族、种族问题。书中对各种族的设定虽然继承自托尔金,但对种族关系的描绘明显取材于现实中的20世纪东欧民族问题。精灵、矮人、半身人等非人种族的处境类似于现实中的少数民族;尼弗伽德帝国以许诺独立建国来鼓动北方非人种族叛乱,颇有二战中苏、德、日等国以输出民族解放运动来作为扩张手段的色彩;松鼠党让人联想起二战期间站在德国一边对抗苏联、在战后却被抛弃的乌克兰反抗军等组织。此外书中还有一些很梗的设定,一些苏东zz笑话小彩蛋,例如特务机构和告密文化、文字狱和出版审查等等。让人不禁感叹,作者果真是一个在社会主义波兰出生长大的作家。

最难能可贵的是,作者对这些的描写,没有如多数通俗文学作家那样流于概念化和漫画化,而是展现出了亲历过相关历史的民族才有的厚重感,和相当宽广成熟的思考。举个例子,关于历史记忆,书中有个片段,在第一次北境战争后不久,来自南方的间谍里恩斯将北方人口中的“辛特拉大屠杀”称之为“辛特拉攻城战”。对北方人来说这是一个绝不会使用的称呼,因为在他们的意识里,这次事件只有一个性质,那便是“大屠杀”,间谍的身份因此被识破。再例如书中所出现的“猎巫运动”,即当灾难发生时,一个社会往往喜欢从内部寻找破坏者,来作为替罪羊和靶子。战争和瘟疫导致了针对女性魔法使用者的“女巫猎捕”运动(这无疑取材于中世纪欧洲的类似迫害活动)。再例如小说结尾对民粹主义抬头的暗示。战争加深了北方诸国人类“非我族类,其心必异”的排外情绪,使原本在卫国战争中站在他们的一边的非人种族战后反倒成为被仇视的对象。诸如此类的思考比比皆是。加上作者的视角并非聚焦于上层,而更多是一个具有愤世嫉俗色彩的旁观者、一个亲历历史变迁的普通人对世相的描绘和思考,使得《猎魔人》可以被称之为某种“社会派”幻想小说。

毫无疑问,作者可以说是个相当愤世嫉俗的人。整部小说最出彩的就是它幽默讽刺的部分,不少片段都在反复嘲弄着人类的愚蠢、自大、偏狭、迷信,有不少睿智的思辨和精彩的吐槽。但这种愤世嫉俗并不是年轻人式的,而是中年人式。正如本书的主角——利维亚的杰洛特便是位云游四方、见过太多善恶以至于时常为此感到疲惫的中年人。

作为第一主角,杰洛特无疑是个代入了作者萨普科夫斯基自身的角色,他云游四方的经历和作者早年作为销售四处奔波的经历十分相似。杰洛特的性格可以说是典型的闷骚,时常将“中立”、“莫得感情”等话挂在嘴上,尽管从实际行动来说他是一个真正具有骑士精神的人。与他相比,书中真正的骑士(例如陶森特的苍鹭骑士们)反倒个个都像是表演型人格障碍患者。杰洛特的另一个可爱之处是他既成熟但又不够成熟。他常自嘲为是个“老派”、“落伍”的人,在变动的时代中感到不知所措,时而没有目标地瞎行动一番来发泄,时而委屈巴巴生闷气令人忍俊不禁。仙尼德岛事变对他“落伍”的世界观无疑是个巨大冲击,此后茫然、颓废的他踏上寻女之旅,一路所经历的不仅是火之洗礼,还是他自身的一场中年危机。

和杰洛特一样,女术士叶妮芙同样属于上个时代,是位不会被“行高尚之事”轻易打动的个人主义者。与他俩相比,特丽丝·梅莉葛德其实更有种青年人的热情和入世精神。特丽丝在索登山战役后成为了一名狂热的爱国主义者,后来又在菲丽芭·艾哈特的影响下,被女术士集会所的“魔法国际主义”所约束,都体现出她与狼叶二人具有根本性的不同。杰洛特和叶妮芙的关系刻画也很值得玩味。叶妮芙身上最吸引人的其实是那股无法被掌控的不确定感,还有直面南墙的孤勇之气。杰洛特既被这种气质强烈吸引,同时又时不时透着股怅然和无力(《冰之碎片》表现的尤其明显)。

如果说作者代入的是以杰洛特为代表的老一辈,希瑞作为年轻一代,则代表了作者对年轻人成长的观察与期许。猎魔人和女术士因为寿命比一般人长,又见过太多世事,本身有种成熟到虚无的感觉。第二卷希瑞出场前,两人一直在互相逃避,很大一部分原因就是这种行将就木的腐朽感。正如叶妮芙所说:“我们只是注定要灭亡、要消失、要被人遗忘的老古董,我们的冬天过后不会再有春天。”而希瑞的出现恰如春之雨燕,她的生命力在《命运之剑》里一出场便令人印象深刻,也成了狼叶二人关系的粘合剂。在她的成长中收到了不少老一辈的保护和引导,例如老隐士维索戈塔——他半生因进步思想而遭迫害和放逐的经历无疑象征了许多东欧知识分子的命运。书中有不少这样的“老人”们,他们愤世嫉俗,被残酷世事打磨到疲惫不堪故作冷语,但以理性和朴素的善良,为疯狂的世界守住了最后的底线。

除此以外,书中还有很多有意思的角色,例如杰洛特的寻女小队。寻女小队的经历是全书我最喜欢的篇章之一,充分体现了《猎魔人》小说的另一个特色,就是那股灰暗背景下倔强的、不合时宜的浪漫主义。成员中,诗人丹德里恩起初让人以为只是搞笑役,但后来发现这个角色其实格外鲜活,是个真正懂何为诗意的人;米尔瓦若生在当代绝对是打拳的一把好手,每次看她吐槽队伍里其他雄性生物都格外有趣;雷吉斯最大的优点是睿智,最大的缺点是喜欢卖弄睿智,他的吸血鬼小课堂是全书最令人印象深刻的讽刺之一;还有“一见希瑞误终身”的卡西尔、“不会说话就多说点”的安古兰、“无可救药的利他主义者”卓尔坦·齐瓦,每个角色都格外鲜活可爱。寻女小队一路上亲历了第二次北境战争期间北方诸国兵连祸结的社会画面,可以说是书中社会派描写和群像塑造的巅峰了。

另一个打动人的主题是关于痛苦、软弱和牺牲。《猎魔人》在这方面可谓继承了斯拉夫人的苦难美学,即“我们因痛苦而高贵”。而对苦难中的人,作者对他们的软弱抱有清醒的认知和宽容,包括他们因为痛苦和软弱而做出的种种错误的、不成熟的举动。因此尽管作者的笔调是愤世嫉俗的、辛辣讽刺的,但始终充满了真诚的人道主义精神和对困境中弱者的无条件同情。主角的软弱和不成熟之处也是他从不回避的。例如希瑞在耗子帮的堕落经历,以及寻女小队的陶森特之旅。耗子帮经历隐喻了青春期孩子在脱离父母保护后,因茫然和软弱而做出的种种不成熟行为。而陶森特之旅对于寻女小队的经历来说堪称点睛之笔。安逸生活的诱惑,和杰洛特充满争议的行为,与后来斯提加城堡之战的沉重形成鲜明对比。中间长达几个月的留白也引人遐想。

在《一点牺牲》这个故事中,作者魔改了《海的女儿》这一童话。美人鱼公主和人类公爵相爱,但他俩一个希望对方喝下魔药长出腿来,另一个希望对方长出鱼鳍和自己去海里生活。两人不欢而散,并互相指责对方不愿意为自己做出“一点点牺牲”。从全书来看,作者从不标榜英雄主义和高尚行为,从不宣扬牺牲和付出,但打动人的恰恰是这种底色下的牺牲和付出。叶妮芙曾吐槽杰洛特看似急于牺牲自己,实则兜兜转转一事无成,只是在做一些没有意义的事情。可到最后,她也认同了杰洛特的做法,踏上了一条牺牲之路,因为“牺牲可以还清人情,展现美德——还能得到女神的恩典,她爱护并欣赏那些出于正当理由牺牲和受苦之人。”作者的执念也正在于此,世界的面貌,是“平衡与智慧并不总是代表冷酷与自私,算计与卑劣,而感情用事也并不永远幼稚”。

萨普科夫斯基声称,自己是自己是在旧的基础上创造出新的东西。《猎魔人》的素材来源可谓十分广泛,前两部短篇小说集魔改各种童话故事,长篇的世界观设定处处映射斯拉夫各民族历史,关于狂烈和赤杨之王的内容甚至联动了歌德的诗歌《魔王》。在书中可以看到他对托尔金的继承,例如种族设定等。但最大差别在于,托尔金的世界十分“古典”,价值观和美感都是古典式的,宗教和神话色彩浓厚;《猎魔人》则十分“现代”,是一个波兰人对二十世纪历史和各种思潮的反映。与《冰与火之歌》相比,尽管两者所描绘的世界同样黑暗残酷,但《猎魔人》出色的社会派描写,和黑暗底色下的浪漫细腻却是前者所不具备的。

这部小说尽管在斯拉夫世界极受欢迎,但在中国的名气远不及前两者。主要原因在我看来,一是浓厚的东欧地域特色,对不熟悉相关文化背景的人形成了阅读壁垒;二是那股与俄罗斯文学相似的、苦大仇深的厚重感,使其明显不如冰火等作品讨喜。还有作品本身的结构和文体问题。系列前两卷为短篇小说集,风格和笔法上和后面几部有很大差别。且第一部短篇集写作时间较早,在我看来,从第二卷的后半部分开始,作者的文笔才完全成熟。后几部小说中作者亦不满于平铺直叙,进行了很多叙事手法上的实验,这些都为阅读增加了障碍。关于作者的叙事手法是否成功当然也是见仁见智,在我看来,卷六就并不算成功,大量闲笔被用于碎片化叙事的转场,割裂了阅读体验。而卷七的内容和形式就结合得更加成熟。总的来说,2、5、7是其中最优秀的三卷。另外,魔戒和冰火的名气都离不开影视改编的成功。《猎魔人》在这方面主要靠cdpr的游戏。尽管《巫师》系列作为游戏非常的优秀,但在剧情上作为《猎魔人》的续集,存在很多容易造成对原著误解的地方。至于最新的猎魔人美剧,只是一部充斥着让人一言难尽魔改的美式爆米花电视剧。而作者本人其实是一个相当“老派”的人,宣称自己对游戏的成功不感兴趣,也不相信有人可以拍好自己的猎魔人。书中那股与大众意识相抗衡的倔强,与ip改编所遵循的消费主义原则本身就是相悖的。游戏的成功给他带来了一大批整天追着他问“杰洛特的真爱是叶奈法还是特丽丝”的年轻粉丝,这在近年来反倒成了一件让作者头疼的事情。在这方面,我非常理解作者萨普科夫斯基的高傲,也希望他能遇到更多知音吧。

网站评分

书籍多样性:4分

书籍信息完全性:5分

网站更新速度:9分

使用便利性:5分

书籍清晰度:3分

书籍格式兼容性:8分

是否包含广告:9分

加载速度:8分

安全性:4分

稳定性:5分

搜索功能:8分

下载便捷性:5分

下载点评

- 实惠(65+)

- 引人入胜(667+)

- 品质不错(312+)

- 速度快(412+)

- 不亏(427+)

- 格式多(267+)

- 体验满分(410+)

- 方便(411+)

下载评价

- 网友 温***欣: ( 2024-12-11 03:51:10 )

可以可以可以

- 网友 郗***兰: ( 2024-12-23 14:10:44 )

网站体验不错

- 网友 敖***菡: ( 2024-12-26 08:39:24 )

是个好网站,很便捷

- 网友 訾***雰: ( 2025-01-01 10:03:36 )

下载速度很快,我选择的是epub格式

- 网友 养***秋: ( 2024-12-16 22:57:35 )

我是新来的考古学家

- 网友 冷***洁: ( 2025-01-05 02:01:38 )

不错,用着很方便

- 网友 后***之: ( 2024-12-25 16:05:05 )

强烈推荐!无论下载速度还是书籍内容都没话说 真的很良心!

- 网友 林***艳: ( 2024-12-12 21:52:00 )

很好,能找到很多平常找不到的书。

- 网友 利***巧: ( 2024-12-22 05:35:05 )

差评。这个是收费的

- 网友 汪***豪: ( 2024-12-09 23:44:54 )

太棒了,我想要azw3的都有呀!!!

- 网友 宓***莉: ( 2024-12-17 06:10:08 )

不仅速度快,而且内容无盗版痕迹。

- 网友 陈***秋: ( 2024-12-13 19:43:33 )

不错,图文清晰,无错版,可以入手。

- 网友 冯***卉: ( 2024-12-29 06:21:52 )

听说内置一千多万的书籍,不知道真假的

- 网友 康***溪: ( 2024-12-19 14:01:03 )

强烈推荐!!!

- 网友 权***波: ( 2024-12-23 03:36:51 )

收费就是好,还可以多种搜索,实在不行直接留言,24小时没发到你邮箱自动退款的!

- 网友 师***怡: ( 2025-01-01 16:20:38 )

说的好不如用的好,真心很好。越来越完美

- 八戒外传 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 9787565507892 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 七彩课堂七年级上册道德与法治 政治人教版 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 世界名牌圣经 奢侈品(全彩) 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 2015办公记事手册 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 中公最新版2014河北公务员考试专用教材名师密押卷申论 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 全新正版图书 英雄壮歌(龙华纪念馆基本陈列)(精) 者_薛峰责_戴燕玲 上海教育出版社 9787572003813青岛新华书店旗舰店 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 流星雨 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- 9787030378545 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

- Messages from the Masters 下载 pdf 电子版 epub 免费 txt 2025

书籍真实打分

故事情节:5分

人物塑造:7分

主题深度:8分

文字风格:6分

语言运用:9分

文笔流畅:8分

思想传递:3分

知识深度:8分

知识广度:4分

实用性:8分

章节划分:6分

结构布局:3分

新颖与独特:3分

情感共鸣:6分

引人入胜:8分

现实相关:3分

沉浸感:4分

事实准确性:9分

文化贡献:7分